Stevedores Against the "Big Five"

Implications of the 1949 Dockworkers' Strike on Indigenous Politics

Note: This essay was originally written for a Political Science course on indigenous Hawaiian politics at the University of Toronto. I studied History and International Relations at the University from 2020 to 2024.

Hawaii functioned as an internal ideological front in the US drive for a global order structured around American financial capital and undergirded by worldwide military preponderance. Developing out of the long duree history of Euro-American colonialism in Hawaii, the anti-communist crackdown following the successful 1949 strike by the International Longshore and Warehouse Union was integral to the successful drive for statehood promoted by haole capitalists. Premised on a competing vision of liberal multiculturalism that purged the ruling class of its most repugnant white supremacist overtones, the statehood movement wielded violent anti-communism to break the back of the interracial Hawaiian working-class — paving the way for Hawaii’s absorption into the American union in violation of Hawaii’s unsurrendered sovereignty. While the Hawaiian socialist labor movement reproduced aspects of the colonial paradigm in their relationship with Kanaka Maoli communities, their destruction at the hands of the American national security state and the islands’ capitalist class removed a potent check on colonial ambitions in the islands, allowing American financial capital and military planners to exploit Hawaii at will.

Hawaii and American Empire

Any discussion of Hawaii’s place in Cold War politics must be prefaced with an outline of the geographic and historic-ideational patterns of American empire. The United States inherited its imperial model from its one-time colonial overlord: the British Empire. After racing across the continent from the Alleghenies to San Francisco Bay, American ‘Manifest Destiny’ turned its eye to the vast Pacific Ocean and the plentiful Asian markets that lay beyond. Its oceanic footprint was mapped over the architecture of Britain’s imperial island network, comprising island nodes tied together by vast sub-sea telecommunications wires and intermittent coaling stations.1 Following the naval doctrine of Alfred Thayer Mahan, American imperialists — especially the two Roosevelt presidents — pursued a massive build-up of American naval capabilities in the early twentieth century and oversaw the acquisition of island strongholds through inter-imperial diplomacy and armed conquest. The 1898 Spanish-American War was particularly productive — adding footholds in Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam, and Samoa to America’s pre-war possessions on Midway and O’ahu.2 Franklin D. Roosevelt’s wily diplomacy with Winston Churchill won the burgeoning American empire control of a vast network of leased military ports through the ‘Destroyers for Bases’ and ‘Lend-Lease’ programs of 1940 and 1941.3 As a matter of course, the indigenous peoples of these islands — if any remained after decades of British occupation — were displaced from their homes to make way for expensive military technological installations and civilian communication nodes.4 In many cases, America’s remote island holdings were utilized for weapons testing — conventional, nuclear, chemical, or biological.5 This American Asiatic thrust forged a “deterritorialized empire…based on global communications along with air, nuclear, space, and other technical systems.”6

As early as 1842 — when President John Tyler rhetorically included Hawaii within a US sphere of influence — the United States recognized the particular importance of the Hawaiian islands to its dream of a trans-Pacific empire. Driven by trade interests in far-off Asian markets, Hawaii was perceived as an indispensable logistical hub to supply, fuel, and arm the American Navy and merchant fleet.7 In 1873, the US launched a covert foray on O’ahu to identify suitable deep-water ports for a massive naval installation. One candidate stood far above the rest: Pearl Harbor — “the key to the Central Pacific Ocean.” The US gained exclusive access to Pearl Harbor with the 1887 ‘Bayonet Constitution’ whose adoption was forced by the haole settler-elite in exchange for removing tariffs on Hawaiian sugar exports to the US.8 In the words of Brigadier General Macomb: “O’ahu is to be encircled with a ring of steel, with mortar batteries at Diamond head, big guns at Waikiki and Pearl Harbor, and a series of redoubts from Koko Head around the island to Waianae.”9 US Marines landed on Hawaiian shores to aid haole industrialists in overthrowing the lawful indigenous government of the Kingdom of Hawaii in the 1893 coup d’etat.10 Five years later, the islands were formally annexed into the US as an incorporated territory and served as a crucial staging ground for operations against the Spanish in the Philippines after the outbreak of war and later as a logistics hub for the brutal American counter-insurgency against the island’s native inhabitants.11 From the beginning of the American occupation of the Hawaiian islands, the US military and white haole elites were bound together by shared interests in Hawaiian industrialization and the preservation of white supremacist rule.12 Since 1947, after the Japanese bombings at the outset of the Second World War and the subsequent declaration of martial law, O’ahu has served as the headquarters of the US Pacific Command.13 Each successive stage of US penetration of the Hawaiian islands launched new waves of Kanaka dispossession, removing native Hawaiians from their lands in the name of national security and tearing up the earth to make way for barracks, dockyards, artillery ranges, and munitions stockpiles.14 As the lynchpin of American Pacific strategy, Hawaiian security and continued American hegemony were, and still are, existential to US military and economic planners.

The Hawaiian Labor Movement

Before discussing its eventual suppression by the anti-communist American national security state, a brief accounting of the Hawaiian labor movement's development is required. The abolition of US tariffs on Hawaiian sugar and the 1898 US annexation of the Hawaiian islands triggered a spate of capital consolidation to meet the high cost of large-scale cash crop production.15 Sugar cultivation and refinement were quickly monopolized under the ‘Big Five’ corporations owned by the white haole elite that held political hegemony after the 1893 coup d’etat and 1898 annexation. “American Factors, C. Brewer & Co., Alexander & Baldwin, Castle & Cooke, and Theo H. Davies & Co.” controlled sugar and pineapple production and dominated the maritime shipping industry through their subsidiary company, Matson. Far more than corporations, the ‘Big Five’ were bound together by dynastic marriages and formally organized in the “Hawaii Sugar Planters’ Association” (HSPA).16 Chronic labor shortages on the islands forced the ‘Big Five’ to import large streams of migrant labor from “China, Portugal, Japan, and the Philippines.”17 These competing and racially divided labor pools were structured in a highly stratified vertical mosaic. Portuguese workers from the Azores were intentionally sought out to “whiten” the labor force and formed a middle strata between the haole and Asian workers, who were subdivided between Japanese and Filipinos. As a colonial possession of the United States, the haole imagined the Philippines as a savage backwater and treated Filipino workers accordingly. The Japanese became a source of deep anxiety for the haole as they embodied the racial terror of a rising post-Meiji Restoration Japan capable of contesting white hegemony as a modernized nation-state with imperial ambitions. Beyond simple white supremacy, anti-Japanese sentiment stemmed from a fear of foreign infiltration and subversion.18 Early attempts to organize workers against brutal working conditions under the “Big Five” foundered on these racial dividing lines, with two significant sugar strikes in 1909 and 1920 collapsing due to fragmented support and active antipathy within a racially stratified proletariat.19

The terrain of class conflict began to change with the passage of the Wagner Act in 1935. While the ‘Big Five’ ignored the New Deal reworking of labor law and heightened repression, the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) deployed agents to the islands in 1937 to personally enforce the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA).20 A single union was primarily responsible for turning the tide on the islands in favor of workers for the first time since American finance capital established itself in the islands: the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU). Primarily concerned with stevedores along the West Coast, the ILWU organized the successful 1934 San Francisco Dock Strike — a training ground for Hawaiian workers on layovers in California ports. The ILWU even triggered the deployment of NLRB agents to the islands through a pressure campaign on the Roosevelt administration. Free to organize after martial law was lifted in October 1944 and backed by the NLRB, the ILWU won passage of the Hawaii Employment Relations Act — casting the cloak of the NLRA over agricultural workers and extending an unprecedented olive branch to large populations of marginalized Filipino workers.21 Martial law served as a pressure cooker for worker discontent, and its end in 1944, alongside a massive push into sugar and pineapple plantations by the ILWU, triggered an explosion in the union’s Hawaiian membership from 900 before the war to over 33,000.22

The most significant innovation that allowed the ILWU to achieve a level of influence over the ‘Big Five’ hitherto unimaginable was its aggressive campaign to cultivate interracial solidarity within the Hawaiian working class. ILWU organizers were left-wing militants that advanced a stark class antagonism as the sole fulcrum around which industrial relations turned: capital and labor. Confronting the daunting power of capital required a united front of interracial labor, without distinction between skilled and unskilled workers. The ILWU reframed the racial narrative of the Hawaiian proletariat, promulgating a party line that identified racial animus as a product of an intentional strategy of ‘divide and rule’ employed by the capitalists.23 Rather than simply deracializing the working class, the ILWU advanced a labor universalism that attended to what Gayartri Spivak terms “radical alterity” — the idea that, in every encounter, there is a ‘secret’ that one cannot fully communicate no matter how much both parties try.24 The ILWU, as Moon-Kie Jung argues, reinterpreted and rearticulated highly particular experiences of racial discrimination through a universal lens of class warfare. This interracial solidarity included Kanaka communities, whom the ILWU identified as having been brutally dispossessed by the same ‘Big Five’ that now exploited agricultural workers and stevedores.25

The 1949 Dock Workers’ Strike

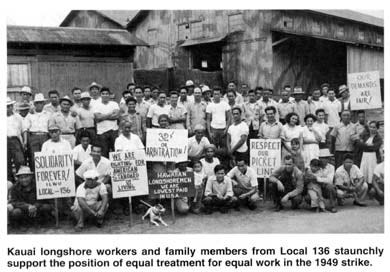

The ILWU’s model of radical interracial unionism faced its greatest test in the dockworkers’ strike of 1949 that lasted from May to October of that year. The union launched the strike, as Koji Ariyoshi recorded in the pages of the union’s left-wing newspaper, the Honolulu Record, over the considerable disparity between the compensation of dockworkers along the West Coast — also under the ILWU — and their compatriots in Hawaii.26 Led locally by ILWU boss Jack Hall and nationally by the renowned union organizer Harry Bridges, the strike mobilized thousands of workers on Hawaiian wharves and shut the ‘Big Five’ owned shipping company Matson alongside the seven largest stevedoring companies in the islands: “Ahukini Terminals, Castle & Cooke, Hilo Transportation & Terminals, Kahului Transportation, Kauai Terminals, Mahukona Terminals, and McCabe, Hamilton & Renny.”27 The strike interdicted $35 million of sugar and 50,000 tons of molasses, cost the tourism industry $4 million, and forced the destruction of 12,000 chicks and eggs. The strike cost the Hawaiian economy $100 million in losses between May and October 1949.28

The strike, which threatened the economic and social stability of the strategically vital Hawaiian islands, also implicated the United States in brutal colonial racism in a territory that was the subject of efforts to reframe American nationalism as a story of liberal multiculturalism. Hawaii was, in the propaganda narrative of public relations guru Edward L. Bernays, to serve as an “alternate vision of American modernity” and an example of democratic nation-building. The strike threw these attempts to obscure American imperialism into chaos, affirming the Soviet line that the US hypocritically harped on human rights violations in the socialist world while simultaneously committing brutal racial violence at home.29 Reactionaries in the islands lashed out at the ILWU, branding the striking stevedores as “communist-led.”30 Lorrin Thurston, a multimillionaire haole who lived in King Kamehameha’s former home, published a weekly “Dear Joe” column addressed to Soviet premier Joseph Stalin that derided the workers as Kremlin stooges. With the backdrop of the Chinese Communist Party’s victory in the Chinese Civil War and rising tensions on the Korean peninsula, these anti-communist broadsides found purchase in the minds of many white Hawaiians. So-called “broom-brigades” of white haole house-wives deployed in the hundreds to ILWU picket lines to harass stevedores with melodramatic signs like: “Communists took over Shanghai, don’t let them take Hawaii.”31

For the workers, their enemies’ furious anti-communism was perplexing. One worker told Koji Ariyoshi: “We sent our sons in the army and we make sacrifices, but when we ask for money due us, they say we take orders from Stalin.”32 Despite constant pressure from the territorial government, which seized the docks a few months into the strike but failed to fill the gap, and growing suspicion directed toward the islands from the House Un-American Activities Committee, the ILWU held out. Finally, on October 6, 1949, the union broke the back of the ‘Big Five.’ From the stairs of his plane back to the national ILWU headquarters in San Fransico, Harry Bridges called capital’s bluff by preemptively declaring a deal to end the strike after “off-the-record” negotiations. The ‘Big Five’ initially denied a deal existed but embarrassingly reversed course an hour later.33 Among the most renowned strikes in American labor history, the ILWU’s 1949 dockworkers strike won its members pay parity with their West Coast counterparts. Still, it also triggered a firestorm that would eventually engulf the ILWU and destroy its radical project.34

Kanaka Maoli

In the decade following the 1949 strike, reactionary haole and the American government crushed the Hawaiian labor movement under the weight of early Cold War anti-communism. With the arrest of seven prominent union leaders in 1951 — “Dwight Freeman, John Reinecke, Jack Kimoto, Charles Fujimoto, Eileen Fujimoto, Jack Hall, and Koji Ariyoshi” — under the auspices of the 1940 Smith Act that the federal government mobilized against leftist groups in the early 1950s, Hawaii fell under the long shadow of Joseph McCarthy.35 While the ILWU membership met the trial and eventual convictions with furious strike actions, the ordeal drove leaders like Jack Hall to break relations with the left-wing of the movement.36 Leftist positions like the ILWU’s demand for a ceasefire in the Korean War and the withdrawal of UN troops, alongside the presence of Ariyoshi — who served as an American military advisor to Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai during the insurgency against Japanese forces in Ya’nan — indelibly colored the ILWU as a ‘red’ organization.37 A 1957 pamphlet written by the editor of the rightist Honolulu Advertiser on behalf of Edward Bernays’ public relations campaign pushing for Hawaiian statehood, for example, utilized the ILWU and its suppression to demonstrate Hawaii’s loyalty to American democratic capitalism.38

The ILWU’s model of radical interracial unionism, specifically centered on the intersection between class warfare and particular experiences of racial discrimination, was a model that the labor movement did not replicate with the same left-wing undertones. This suppression of left-wing unionism — which held a knife to the neck of the US capitalist class by shutting down all commerce in a strategically vital archipelago for over 150 days — bears direct implications on the conditions and relative political power of indigenous Kanaka communities.39 While the connection may not appear immediately obvious, the loss of a radical fulcrum at the point of production was a tremendous blow to indigenous Hawaiians’ ability to effectively disrupt the machine of capital accumulation that feeds the fortunes of Hawaii’s colonizers. The ILWU was not a Kanaka organization. It did not center on indigenous interests, nor were its ranks heavily populated by Hawaii’s native population; however, the union’s proven pattern of interracial organizing, particularly concerning marginalized Filipino agricultural workers, alongside the labor movement’s repeated invocations of Kanaka dispossession in the 1893 coup d’etat and the 1898 US annexation, leave tantalizing alternate histories of Hawaii at the outset of the Cold War open to speculation.40 The shared enemies of indigenous communities and the socialist labor movement — American financial capital and the US military occupation — both rely on the free flow of goods from Hawaiian ports. Before the haole destroyed the union, the ILWU’s stranglehold on Hawaiian wharves and its victory over the ‘Big Five’ in the 1949 strike proved that the same strategic attributes that render Hawaii indispensable to the American empire are also critical vulnerabilities.

Despite the considerable opportunities for Kanaka organizing that were foreclosed upon by the US government’s crusade against the ILWU, the union and the socialist movement in Hawaii were not perfect allies to indigenous communities. John Stuart Mill’s foundational text on liberal ideology — On Liberty — outlines two circumstances under which society might justly restrict an individual’s liberty: to protect others from harm and to shield children from self-inflicted injury resulting from their partially formed minds. Mill, writing in the context of the East India Company’s rule over the Indian subcontinent, extends the latter condition to encompass peoples in a state of ‘civilizational infancy’ — that is, populations who do not conform to the Western, utilitarian norm of seeking ‘progress’ at all cost. Populations that fall under this category could be justly ruled through “vigorous despotism” until they are properly ‘trained’ to be “capable of higher civilization.”41 In the post-war context of the early 1950s, this liberal logic of ‘improvement’ as a prerequisite to civilization metastasized into a language of ‘development’ in the epistemological mold of ‘Modernization Theory,’ which argued that material development guided by Western advisors under the firm rule of an authoritarian government was an essential prerequisite to political liberty and democratic nation-hood.42 The ILWU, while aligned with the socialist tradition rather than the liberal-capitalist one, maintained a similarly paternalistic view of Kanaka communities to some degree. In the ILWU’s narrative of the 1893 overthrow and 1898 annexation, as Dean Saranillio argues, indigenous Hawaiians are passive “victims of white supremacy” who could not “organize a masculine resistance or create a nation of any substance.”43 The Hawaiian left-wing remained stuck in a mode of ‘settler thinking’ that allowed sympathy for Kanaka and disdain for their colonizers; however, it also made “Hawaiian modes of life and self-governance seem logically impossible and irrelevant to the present.” In this way, the ILWU and the Hawaiian socialist left were deeply embedded within the imperial thought universe of the US colonizers.44

Hawaii’s position as an outpost of American empire in the Pacific rendered it a centrally important internal front in the ideological battle of the early Cold War. Strategically vital to American military interests and playing unwilling host to the US Pacific Command and a large concentration of American troops for most of the 20th century and into the 21st, Hawaiian power relations and its internal battles between competing interests cannot escape the intervention of Washington. The 1949 ILWU dockworkers’ strike, which placed a stranglehold on the neck of the haole controlled ‘Big Five’ corporations and stirred a furious anti-communist backlash from the federal government after its successful conclusion, demonstrated the strategic potential of militant labor organizing to pierce holes in the armor of American finance capital in the Hawaiian islands. Interracially organized around the central pivot of class warfare, the ILWU mobilized workers across racial lines for the first time in Hawaii’s history and won tremendous victories as a result. The potential for interracial solidarity in disrupting American finance capital at the point of production to extract significant concessions bears clear relevance to the comparatively weak position of Kanaka communities. While the ILWU and the socialist labor movement expressed profound sympathy with Kanaka and condemned their colonizers, they remained epistemologically incapable of recognizing indigenous forms of resistance and reproduced colonialist narratives of native impotence. Despite these profound shortcomings, the ILWU’s successful strike actions in the mid-20th century remain a potent model for future organizing against American finance capital and the military occupation of the Hawaiian islands.

Notes:

1. Ruth Oldenziel, “Islands: The United States as a Networked Empire,” in Entangled Geographies: Empire and Technopolitics in the Global Cold War, ed. Gabrielle Hecht (The MIT Press, 2011), 15, https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9780262515788.003.0002.

2. Ibid, 16.

3. Ibid, 19.

4. Ibid, 26.

5. Ibid, 22.

6. Ibid, 22.

7. Kyle Kajihiro, “The Militarizing of Hawai‘i: Occupation, Accommodation, and Resistance,” in Asian Settler Colonialism: From Local Governance to the Habits of Everyday Life in Hawai’i (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2008), 173.

8. Kajihiro, 175.

9. David Keanu Sai, “The American Occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom: Beginning the Transition from Occupied to Restored State” (Ph.D., United States -- Hawaii, University of Hawai’i at Manoa), 157, accessed February 26, 2024, https://www.proquest.com/docview/304605311/abstract/83D338EFDFDE46F6PQ/1.

10. Ibid, 162.

11. Ibid, 153.

12. Kajihiro, “The Militarizing of Hawai‘i: Occupation, Accommodation, and Resistance,” 176.

13. Sai, “The American Occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom,” 157.

14. Vernadette Vicuña Gonzalez, Securing Paradise: Tourism and Militarism in Hawai’i and the Philippines, Next Wave (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013), 24.

15. Moon-Kie Jung, “Interracialism: The Ideological Transformation of Hawaii’s Working Class,” American Sociological Review 68, no. 3 (June 1, 2003): 378, https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240306800304.

16. Alan D. Boyes, “Red Hawaii: The Postwar Containment of Communists in the Territory of Hawaii” (Master of Arts in History, Honolulu, University of Hawai’i, 2007), 19.

17. Jung, “Interracialism,” 378.

18. Ibid, 379.

19. Ibid, 380.

20. Ibid, 381.

21. Ibid, 382.

22. Ibid, 383.

23. Ibid, 385.

24. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, A Critique of Postcolonial Reason: Toward a History of the Vanishing Present (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1999), 384.

25. Jung, “Interracialism,” 387.

26. Koji Ariyoshi, “Longshoremen Expect Long Siege; Rank and File Solid,” Honolulu Record, 1949, 1.

27. Boyes, “Red Hawaii,” 14.

28. Gerald Horne, Fighting in Paradise: Labor Unions, Racism, and Communists in the Making of Modern Hawaiʻi (Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2011), 179.

29. Dean Itsuji Saranillio, Unsustainable Empire: Alternative Histories of Hawaiʻi Statehood (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018), 133.

30. Horne, Fighting in Paradise, 176.

31. Ibid, 182.

32. Ariyoshi, “Longshoremen Expect Long Siege; Rank and File Solid,” 3.

33. Koji Ariyoshi, “Employers Confim Accord with ILWU After Denial,” Honolulu Record, 1949, sec. Labor Roundup, 1 and 4.

34. Horne, Fighting in Paradise, 193.

35. Ibid, 235.

36. Ibid, 237.

37. Ibid, 240.

38. Buck Buchwach, “Hawaii, U.S.A.: Communist Beachhead or Showcase for Americanism?” (Hawaii Statehood Commission, 1957), 18.

39. Boyes, “Red Hawaii,” 40.

40. Saranillio, Unsustainable Empire, 135.

41. Uday Singh Mehta, Liberalism and Empire: A Study in 19th Century British Liberal Thought (Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press, 1999), 106.

42. Mark Mazower, Governing the World: The History of an Idea, 1815 to the Present (New York, USA: Penguin Books, 2012), 291.

43. Saranillio, Unsustainable Empire, 150.

44. Ibid, 153.

Bibliography

Ariyoshi, Koji. “Employers Confim Accord with ILWU After Denial.” Honolulu Record, 1949, sec. Labor Roundup.

———. “Longshoremen Expect Long Siege; Rank and File Solid.” Honolulu Record, 1949.

Gonzalez, Vernadette Vicuña. Securing Paradise: Tourism and Militarism in Hawai’i and the Philippines. Next Wave. Durham: Duke University Press, 2013.

Horne, Gerald. Fighting in Paradise: Labor Unions, Racism, and Communists in the Making of Modern Hawaiʻi. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2011.

Jung, Moon-Kie. “Interracialism: The Ideological Transformation of Hawaii’s Working Class.” American Sociological Review 68, no. 3 (June 1, 2003): 373–400. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240306800304.

Kajihiro, Kyle. “The Militarizing of Hawai‘i: Occupation, Accommodation, and Resistance.” In Asian Settler Colonialism: From Local Governance to the Habits of Everyday Life in Hawai’i, 170–94. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2008.

Mazower, Mark. Governing the World: The History of an Idea, 1815 to the Present. New York, USA: Penguin Books, 2012.

Mehta, Uday Singh. Liberalism and Empire: A Study in 19th Century British Liberal Thought. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press, 1999.

Oldenziel, Ruth. “Islands: The United States as a Networked Empire.” In Entangled Geographies: Empire and Technopolitics in the Global Cold War, edited by Gabrielle Hecht, 0. The MIT Press, 2011. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9780262515788.003.0002.

Saranillio, Dean Itsuji. Unsustainable Empire: Alternative Histories of Hawaiʻi Statehood. Durham: Duke University Press, 2018.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. A Critique of Postcolonial Reason: Toward a History of the Vanishing Present. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1999.